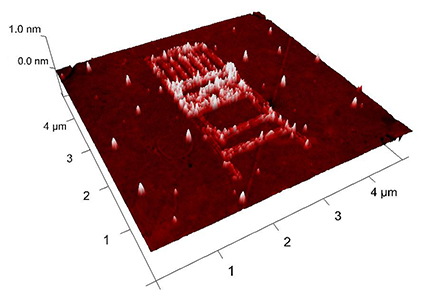

Vladimir Todorović, One and Five or Six Chairs, nanolitography, 2003-2004.

Dejan Grba: Your work is characterized by the exploration of incident and interaction between the medium and the observer. How did you get interested in these qualities?

Vladimir Todorović: While I was working in Serbia I was often uninterested in the local and global art scene. The banality of self-referential art, the romanticized notion of the 21st century artist as the artist of the 19th century, the belief that Serbia is excluded from the global art scene, the dynamism and intensity of all aspects of life except the professional ones, all these things have probably produced a saturation that saved me from getting involved in the exploration of that exotic historical and political context. The result was art that uses chance, but in a machinic, systemic, structural and random way. It was manifested in emphasizing and questioning the media used in the works that, like all media-based instruments, (do not) require an active participation of the audience.

After using new technologies more actively, I realized that every ‘media conditioned’ person inevitably projects that conditioning to the media he or she uses. I made my first video work while I was a third grade student and I used a computer program which made 100 seconds of video out of 2500 images and 2500 audio segments, and played them back in a random sequence. Video, as a linear and now a traditional medium, was treated in non-linear way by the random rearrangement of the database. I noticed this sort of ‘media conditioning’ in drawing and in any other mode of expression I used.

Roman Signer was one of the artists whose work has influenced you quite significantly.

Sol LeWitt worked with algorithmic principles (that are widely used today in software art) by which a drawing, for example, results from the mechanically applied set of rules, in the same way as the computer processor executes the program. These principles resulted in variable forms and unpredictable manifestations. In Signer, the instructions resulted in actions, explosions and trivial events. I recognize the similar approach in paintings and video works from my ‘Serbian period’, in which I used different machinic strategies trying to free my work of any personal touch.

Signer’s influence was probably more significant in that period than LeWitt’s, although now I think that both these approaches are self-referential and function primarily within the platform of modifying the art history and thus possibly improving the environment, but that is where they end. Now, I perceive Signer’s art in the same way as I would consume a good commercial product, a good football player or a pop-icon. I do not want to claim that Signer’s significance is greater or smaller than, say, Michael Jackson’s, but that it is difficult to value the achievements or subversiveness of such figures. I’ve had many other influences in visual arts, especially in film (Tarkovsky, Herzog, Tsukamoto) and in music from Hendrix and Coltrane, The Sex Pistols, Laibach and Fela Kuti, to the electronic sound of Monolake, Vladislav Delay, and Alva Noto. The influences were so strong that at one point I made a work about them, titled Self-Portrait. Later I tried to get rid of all links with the past and of all quotations. I believe that I have brought that reference level down to a certain minimum, but there is, of course, always room for improvement.

A more important, although maybe not so explicit, influence to my artistic education was the everyday life in Serbia in the Nineties. In that period, a common day in Zrenjanin, a town where I lived, could be described like this: with no electricity for half a day, I am trying to talk to some guys from the University of California over a heavily overpriced 3kb/s dial-up internet connection, and one evening my street discovers that a Tomahawk cruise missile was to fly over us, so we all come out to observe this phenomenon which lasted just a couple of minutes. In an almost romantic atmosphere, without electricity and in total darkness, people come out to the street with a sense of belonging and collective participation, and watch the spectacle. The Tomahawk glides over in silence and everything somehow seems very clear. We did not know the mission of this complex instrument and we were at a strange, semi-secure distance. I try to forget this totally sublime scene and to think of Constable’s, Kiefer’s or the Chapman Brothers’ works as of something stronger and supposedly more interesting. If we look at all this in the context of visual arts whose effect should be attained or somehow surpassed, maybe we can get the reasons for my saturation with (un)usual art which has been the (in)direct product of that context.

Your recent work reflects certain activist ambitions.

Regardless of the whole context, the impressiveness and the effect of the ‘Tomahawk event’, I believe that art still can achieve such level of spectacle. However, it seems that today the function and purpose of art spectacle are less important. I think that society is in such a state that it’s hard to believe that any effect could change or improve it. Activist art can trigger some future ideas whose forms and materializations we do not anticipate, but activism in art operates in the same way as, for example, Cubism or Suprematism earlier. I believe that it is an already obsolete form because of the tremendous speed the world is changing, and that we need to work more to define the new forms, which requires a global insight and understanding. I believe that it is rather careless to get engaged in most issues commonly addressed by contemporary art such as museum politics, identity, transgression, demonstration of virtuosity, personal stories or self-improvement, and to consciously contextualize all that with the ideas of progress or ideological agendas defined by the economy, prosperity and civil rights. In the end, it all comes down to the NSK strategy of demystifying the political ideologies by overstatement. This NSK approach alone can put all works dealing with similar issues in the position of replicas or bad students’ attempts. I think that it is arrogant to engage in art that functions like furniture, and I am trying to find a way of dealing with the world through some new forms. I believe that the situation can be improved and I would surely rather be a businessman for the sake of art than an artist for art’s sake. Being a businessman for business’ sake is, of course, the worst option.

In that sense, what do you think of net-art and of the possibilities offered by the networking technologies?

Rhizome, the online art association in the U.S. and technophiles gathered around it, made a work called Starry Night that belongs to the category of net-art. It is a web interface that looks like a starry sky, the stars representing the art works from Rhizome’s database and the stars’ magnitude varies according to the number of people accessing the corresponding art works. Here we have a metaphor of the Internet as the open space or the sky. That is, of course, too good to be true. But this metaphor bears an idea of the new network systems in which the artist is an independent point, increasing, decreasing or falling. A lot of stuff on the net can work like the sky from a Van Gogh’s painting, but that’s not the way the art value systems function and it is much easier to evaluate engineering or scientific achievements than art. The net-art has specific rules so it becomes important to know how to place a ‘star’ on the ‘sky’. Actually, the same rules apply to the global museum and gallery system in which the artist must take a certain branding path in order to adapt to that system and to become its part. In that respect, the information technologies are of no help. But concerning the information access and technological possibilities, the Internet is a considerable platform which can be viewed as a transparent space with no beginning or end, a space that originally had no laws except the topological laws of its encoding (which is an almost ideal anarcho-communist infrastructure) but that is gradually getting organized and governed, primarily by financial interests and only partially by pure reason or creativity.

You operate within a wide media and conceptual range that, until the recent affirmation of artists’ pluralism, has been widely regarded as risky. How do you feel working without a clearly defined stylistic identity?

Maintaining a unique stylistic identity is culturally conditioned, and I think that it is a result of rigidity and need for something concrete. I don’t think it is bad, though, and there are many good artists with a boringly solid style. Artists, except maybe those who were discovered posthumously, predominantly use this strategy because it somehow fits into history. Just as I experimented with visual expressions and methods in drawing, I later used different materials, nanotechnology, paintball, computer games… The possibilities of new media art are virtually limitless and I believe that the art based in self-improvement is marginal and not worth bothering. New technologies, simultaneously novel and obsolete, offer the things that have never been used, done or tried before, which could create radically new situations.

With exhibitions from Vienna, Prague, Wroclaw and Berlin, to Fresno, New York, San Hose, Sao Paolo and Rosario City, to Singapore and Chang Mai, you have been creating a dynamic career which is, however, almost unknown in Serbia. Knowing the mentality of the local art scene, that does not surprise me. How about you?

Maybe I shouldn’t be surprised. It would probably be best to say that one day this situation will change. Basically, if an artist is not willing to get in direct contact with power centers – galleries, curators, the media – he or she is doomed to a certain level of anonymity. In Serbia, I did not look for such centers and could not fit in their ways of functioning. That forced me to do a lot of things on my own, without connections or support. Even when I was in some contact with institutions during Milošević’s regime, I always felt used by that system, which by itself was not as bad an experience as the sense of inaccessibility and hierarchy in these institutions where some people behave at the verge of normality (in assuming the position of the most important persons on the planet when they talk to local artists while being pathetically servile when facing someone from abroad). The consequences of such attitude are extremely superficial and derogatory. That is why the ‘stars’ of Serbian music, film and visual arts are ruining generation after generation of young people. Maybe it would be underestimating to say that Serbian art had never had a significant global impact, but we need to be smart and overcome our marginality instead of deepening it and criticizing it.

Remont Art Magazine, No. 15, Winter, Belgrade, 2006.