The Problematic of National Identity and Social Engagement in the Contemporary Art Practice in the Balkans

In the year 2003, the project Balkan Konsulat organised by >rotor< gallery from Graz hosted a series of exhibitions based on of the cities of Southeast of Europe. Along the main events, the guest curators were asked to choose two artworks to be exhibited on one of the billboards placed in the city, which would then be later published in the Austrian daily newspaper der Standard and travel to other contributing cities. Stevan Vuković, the curator of the Belgrade exhibition invited Dejan Grba, and his work, The Deceased: Archive.

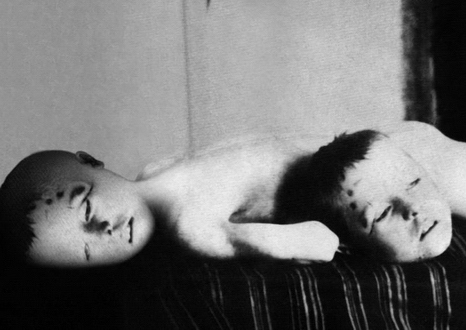

Dejan Grba, The Deceased: Archive, bilbord i reklama u novinama, Grac, 2002.

This archival image was actually preceded by a series of work titled The Deceased comprising photographs, in the artist’s description, ‘of (mostly younger) people who perform a scene of their own imagined death as if it would have happened in this period of their life.’ Referring to Roland Barthes’ use of a photograph a young man sentenced to death and waiting for his execution, and to a general human tragedy by facing the death, the images in the series bore nevertheless the traces of a situated, locally specific fear of death in the young imaginations that have severely suffered from an irrationally bloody decade during the collapse of Yugoslavia. More than being about death, these performative enactments of one’s own death (or rather murder), in a relatively younger age, was aimed to pursue an intimate understanding of daily politics of being alive.

The Deceased: Archive designed to complement this previous series was actually operating with a methodology that was opposite to the previous photographs. This time the scene of death was based on archival material that unavoidably called back the notion of truth. The historical photograph employed here originated from the period of World War II. The depicted image is a corpse of a young boy lying on a table with his severed head placed besides his innocent body. A basic digital intervention of Grba was transferring the severed head back onto the decapitated torso, reconstituting the wholeness of the body, and bringing it back to life – yet by retaining also the severed head, that is the trauma, the horror, the visual affect in its place. In his concept description Grba made it clear that he was aware of the ‘potentially disturbing nature’ of the work, and he invited the viewer to step beyond contextualising the image and to ‘overcome the possible (and quite probable) unease’ through an appeal to ‘self-introspection’. However, there were some people who found the image disturbing and who were not in favour of dis-contextualising it. Der Standard stated that they would not publish the image on their papers, and the partner of the exhibition series in Sarajevo said that they would not display it on a billboard in their city.

The objection of der Standard was probably related to their disinclination to bring haunting images of a horror experienced somewhere close by to the well-protected, family-based, social-democrat households of their readers. But, the discomfort of the associates in Sarajevo was undoubtedly related to the direct, specific and deeply traumatic experience of the siege and terror inflicted on their city, rather than a generic visual disturbance by displaying human agony, disintegrated human bodies and so on. It was a statement about Sarajevo’s unpreparedness for being treated by a process of abreaction. The correct time to deal with that trauma will be decided by the city itself, they implied – perhaps an unspoken suggestion whispered – and not by an artist coming from Serbia.

Was Grba’s plea for the audience inhabiting the public space not to over-contextualise his piece (that is, not to contextualise it through the overwhelming signifier of the country he originates from) bound to fail from the start? Should he have been more attentive to the extremely delicate fragilities of the region by pursuing a politically correct reservedness? Wasn’t there a danger of echoing the ideological rhetoric of the Milosević regime that constantly construed Serbians as the initial victims of the disintegration process of Yugoslavia and the following wave of ethnical cleansing and massacres? Should Grba have remained rather within the restrained, speechless posture of ‘shame’, which is something completely different than the sense of ‘guilt’? But, what about the trauma of the masses that are reductively clustered under the name of the oppressing state apparatus, the trauma of the victims of the Milosević regime within Serbia, of a generation that had to witness the demise of its own youth? In that circumstances, can we afford to ask for a ‘pre-conscious self-censorship, a way of obscuring a world that could no longer be presented in comprehensible terms?’

How far can we identify the content of an artwork with the burden of its historical references, and the artist with his/her national identity? To what extent can an artist distance or divorce him/herself from his/her national identity, and by which strategies? These are complex issues toward questioning to develop a creative strategy, which interacts with a new paradigm and lays another set of questions in examining how to remain operating on the social context of a particular region without being trapped by the centripetal force of the national identity? Do these lines belong merely to a conspiring ‘Turkish’ guy with the uncannily flag-like surname ‘Kosova’?

Erden Kosova, Zone of Tension, from the text The Problematic of National Identity and Social Engagement in the Contemporary Art Practice in the Balkans, conference paper, 2003.