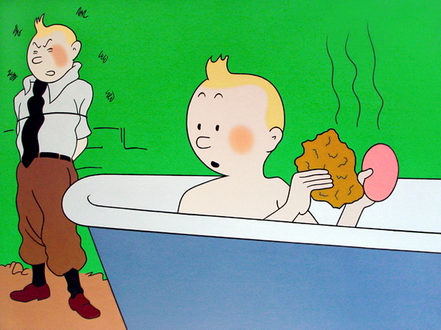

Dejan Grba, Ghosts, oil on canvas, 1998-2001.

The spirit of adventure permeates one of the most famous cartoons – The Adventures of Tintin – not only denoting its literary references and dynamic period of the late Thirties in which it was created, but also promoting action for its own sake, as a supreme reason or cause. Virtual heroes often have such destiny because they never get old and their adventures have to be interesting to each new generation of cartoon readers. With Tintin, something paradoxical happened: the very cartoon got old instead of its hero. The script became slow, the inflated text balloons suppressed the action, and the word overpowered the image. Aging of Tintin’s creator, Belgian Hergé,[1] had influenced the overall structure of his work. At first intentional but later on increasingly subconscious, draughtsman’s identification with his hero mutated Tintin from an omnipotent, somewhat unscrupulous youngster into a precautious sage. Wanting to render his hero as realistic as possible Hergé sends Tintin, who works as a journalist for Le Petit Vingtième,[2] to cover the breaking news events and to solve problems all over the world, from the Land of Soviets, Capone’s America, and Egyptian pyramids to oil war, Israeli-Palestinian clash, Moon landing, and the Yeti hunt. Hergé had set up the reality as a key principle and combined it with the increasingly realistic drawing. This need for authenticity thus reversed the cartoon’s virtuality that was additionally accentuated by the staged promotions of early episodes of Tintin’s adventures, in which the ‘real’ hero appeared ‘live’.

All these aspects are conceptualized by Dejan Grba’s series of paintings, named after one of Tintin’s adventures The Blue Lotus (Le Lotus Bleu). The series comprises various aspects of Tintin’s portrait, derived from different situations and episodes. Grba subjects these portraits to a rigorous formal process in which he purifies and intensifies the visual substance of his model. As opposed to Pop Art painters who took comics as mass-cultural products and brought them to the realm of art while preserving their original contents almost literally, Grba’s interpretation of Tintin’s image involves ambivalent corrections and formal combinations that accentuate the artist’s personal insight and point to the unpredictable implications. By combining graphic and metonymic elements from different scenes and by applying flat, carefully articulated colour surfaces, he achieves an unexpected visual tension. Using Tintin as a semantic paradigm of adventure, Grba records his own venturing through the perilous reality of the last ten years in Yugoslavia. The artist’s strong identification with the cartoon hero refers to a delusiveness of our lives throughout that period, marked by the obliteration of boundaries between fiction and reality.

Tintin’s adventure The Blue Lotus takes place during Sino-Japanese war in 1931. The plot is built upon the fact that everything turns out to be something completely different, and that nobody is what he or she claims to be. This play of obscured identities and hidden agendas yields a key of Grba’s endeavours to load his paintings with total unpredictability. This exhibition therefore functions as an unsolved riddle, without the easily intelligible sense. It is in fact a testimony of our recent ‘adventures’ with existential threats and spiritual annihilation, expressed by depicting the image of the Other in which we reflect ourselves most easily. This twisted compendium of expressions des passions de l’ame représentées en plusieurs albums des bandes dessinées d’après les dessins de monsieur Hergé,[3] leaves no doubt about which escapades are addressed and what debris they caused in our hearts. Violation of the human essence in Grba’s paintings is achieved through ironic, even sarcastic maltreatment of the painted hero who is unable to transcend his cartoon as a metaphor of our own failure to escape the confining stream of reality. Even the titles of these paintings indicate states of frustration, tension, mimicry, delusion, discomfort, or numbness, closing the circle of victimization at the verbal level.

Dejan Grba’s autobiography, encapsulated in facial and emotional expressions of his childhood’s favourite cartoon hero, reveals the scale of affliction that so thoroughly distressed our core selves and our earliest memories, depriving us of everything – of our minds and souls, our love and faith, even our last hopes. All we had been left with was a submission to the oblivion and opium puffs of The Blue Lotus.

Čedomir Vasić, Dejan Grba’s Blue Lotus, The Blue Lotus exhibition catalogue, Remont Gallery, Belgrade, 2001.