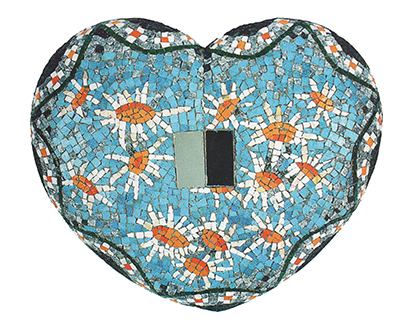

Dragana Knežević, Licitar Heart, mosaic, 1996.

Oil used for lubricating clutches and springs of musical instruments holds dust in a special way. Its sinister smell in the resonator and keys of melodica incites strong memories of the traumas of growing up. The horror of early intuitions of life's fragility and uncertainty somehow creeps from the scent into the sound that becomes ambivalent: emotionally satiated and hollow at the same time. The sound of melodica carries the ambiguity of experience and many grown-ups avoid hearing its sound again.

Melodica is a pocket counterpart of street organ and in its tone trembles a deafening cacophony and hot atmosphere of a fairground.[1] Those who were taken to amusement parks in Belgrade in their childhood during the seventies, remember the disturbing mixture of loud sound and sugary taste of compulsory amusement. Cunningly positioned in front of the Zoo, which itself hinted at unhealthy staleness, the amusement park looked as a place for stigmatizing the frustrations of both staying and senile immovability. The children, most of whom have complex mental capabilities for amusement, were taken there to fit their future inclinations to what the world would offer them later on.

That squeezing of creativity into the existing models was crowned by buying a gingerbread (licitar) heart – an absurd piece of dough with sugar topping and appropriately tasteless embodiment of regimentation. A coloured heart is kept on the wall or carried around one’s neck as a totem of an unpleasant command of social trends of forced relaxation and forced joy, i.e. towards consumerist compulsion. And, although the child’s initial adaptation to its origins, blood and soil often ends up with a headache, its potential individuality is gradually replaced by sullen acceptance of the conventions, before becoming reliably immune to freedom. Finally, as expected, boy meets girl, and if he loses her, he has to find another one because he must satisfy the unbearable and unspoken imperative of flow, he must alleviate his portion of uneasiness and find the peace of tram lovers’ entwined fingers – the peace of pigeons, dogs, plastic flowers, costume-jeweler, fast food and violet colour.

It is not easy to make an opinion towards the new works of Dragana Knežević because they, like the sound of melodica, contain a hardly discernable and hardly bearable ambiguity. Her mosaics of embroideries and licitar hearts refer to (re)examination of kitsch but, while in such artistic procedures the distance is achieved through sophisticated visual devices, here even the material itself balances at the edge of acceptability or ‘good taste’. The works are made with artificial, glassy tesseræ (Venetian paste) that most of the traditional mosaic makers despise because of its plain and ‘unnatural’ appearance. (The question remains, of course, to what extent mosaic itself is natural and how the notion of naturalness can be defined at all.) These pieces hardly offer the viewer any stable ideological position and it is precisely this vagueness, this avoidance of the artist to take a clear stand towards her works that constitutes their main value.

An obvious author’s attitude can somehow diminish the work and reduce it to an intelligible code, to a set of instructions for quick processing and consummation. In such works, the appeal is immobilized or even cancelled and all the excitement (if there is any) is channeled and reduced to a predefined plane of contemplation. Some artists, however, deal with the very danger of ambivalence itself and their poetics are defined by uncertainty and indecisiveness. Actions of such artists undermine the basic concepts of the attitude towards art and reality, remaining authentic regardless of the context. Their works require the viewer’s self-consciousness and readiness of to abandon former criteria and to find the new, more suitable ones – they are a call to self-examination and rearticulation.

The works of Dragana Knežević are such achievements with high ‘risk level’, whose conceptual structure wittily surpasses the traditional limitations and fach-idiocy of the visual media. Here, the lightness of coloured licitar drowns in a mass of concrete, and the gilded crispness of embroidery frames fades into wasted urban vistas.[2] Artificial stones and plastic applications vibrate in a daring challenge to the conventional taste and cultural co-modification, hinting with their colours a gruesome melody of the street accordion player. Little doors open, the tiny mirrors shine cheerfully and maliciously, perfidiously bringing back the doubled image of the viewer: the one who can leave at any moment, but doesn’t want to, and the other one, who desperately wants to leave, but can’t.

Dragana Knežević, Licitar Hearts and Needleworks, exhibition catalogue, Faculty of Fine Arts Gallery, Belgrade, 1996.