References are among the most important contextual factors of art. Thematically scrutinizing a number of conceptual, motivational and compositional connections between various artworks, this lecture accompanies the lecture I Cite (Very) Art on (re)creativity in contemporary art.

Referencing is a broad term in visual arts used to denote different relations, connections and borrowings, ranging from reminiscences, reflections and dedications, to citations, interpretations and questionings, to free copies, imitations, forgeries and rip-offs.

A fine example of self-referencing is J.S. Bach’s variation on a theme B.A.C.H. that appears in several of his compositions, such as The Art of Fugue (BWV 1080) from 1745-1751. I used it as a title of this lecture which, however, adresses the more prevalent references not to the artist's own but the the works and solutions of other artists. Instead of designing it conventionally, as a systematic overview of cases and literature, I based it only upon the referencing examples that I notice or recall casually in order to illustrate the frequency, complexity and diversity of references in art and culture.

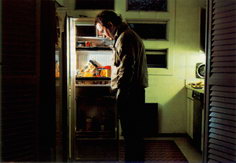

Fridge

Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Mario, 1978.

Joel Schumacher, Falling Down, 1995.

David Fincher, Fight Club, 1999.

The theme of ‘existentialist’ staring in the refrigerator, masterfully enacted in Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s photograph Mario (1978), is widely exploited in film, as a so-called ‘fireplace view’ in which the camera acquires the humanly unattainable positions.

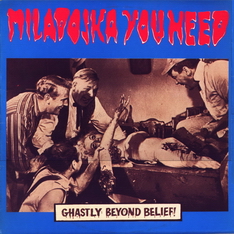

Ghastly Beyond Belief

Herschell Gordon Lewis, 2000 Maniacs, 1964.

Miladojka Youneed, Ghastly..., 1987.

Dejan Grba, Kraftwerk P-b-M, 1998.

The ambivalent seductiveness of the official announcement that warns the cinema or TV audience about explicit or radical contents, was employed in splatter movies such as Herschell Gordon Lewis’s Blood Feast (1963) and Two Thousand Maniacs (1964), but also on the record Ghastly Beyond Belief (1987) by Slovenian band Miladojka Youneed, which was conceptualized as a musical transposition of a horror film, and in 1998 I paraphrased it in the original version of generative video Kraftwerk P-b-M. It was pathetically exploited in Michael Moore’s documentary film Capitalism: A Love Story (2009).

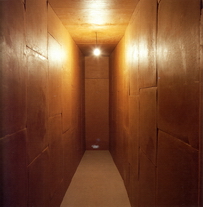

Wax

William Friedkin, The French Connection, 1971.

Wolfgang Laib, S.E., 1997.

Andreas Gursky, Plenarsaal I, Brazilia, 1994.

The pastel-waxy-claustrophobic perspective, visible in a couple of brief sequences in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), is reflected in Andreas Gursky’s photograph Plenarsaal I, Brazilia (1994) and carefully reconstructed in Wolfgang Laib’s installation Somewhere Else: La Chambre des Certitudes (1997).

Well

Andrea Mantegna, Oculus, 1465.

Zoltan Korda, Sahara, 1943.

Fra Andrea del Pozzo, Camere di San Ignazio, 1681-86.

The compositional concept of Oculus (a circular opening in the ceiling) that Andrea Mantegna used in a Camera degli Sposi fresco in Mantova in 1465, was developed to baroque proportions and combined with the anamorphosis in the work of Fra Andree del Pozzo (1642-1709) and cited in Zoltan Korda’s film Sahara (1943).

Arm in the Hand

Anwar el Sadat Assassination, 1981 (detail).

Akira Kurosawa, Ran, 1985.

Steven Spielberg,Saving Private Ryan, 1998.

The horrifying and anthropologically based motif of losing a hand or an arm as a symbol of humanity was broadcasted globally and mainly uncensored in the coverage of an army parade that turned into a spectacular assassination of the Egyptian president Anwar el Sadat in 1981. The stature and gesture of one of the VIP box guests wounded in that assassination were repeated four years later in Akira Kurosawa’s film Ran, and thirteen years after that in Steven Spielberg’s film Saving Private Ryan.

Arrow in the Eye

Andrea Mantegna, Martyrdom of St. Christopher, 1451-1455.

Andrea Mantegna, detail.

Akira Kurosawa, Ran, 1985.

Arrow in the eye, which can be regarded as one of the key metaphors of the linear perspective in Renaissance,[1] was visualized in Andrea Mantegna’s fresco Martyrdom of St. Christopher (1451-1455), and recreated as a vignette in Akira Kurosawa’s film Ran (1985).

Eiichi Kudo, Eleven Samurai, 1966.

It seems, however, that Kurosawa too was eager to learn or perhaps to borrow from his colleagues such as Eiichi Kudo and his film Eleven Samurai (Ju-ichinin no samurai) from 1966, the last in the jidaigeki series on samurai revenge that includes Thirteen Assassins (Jûsan-nin no shikaku) from 1963 and The Great Duel (Dai Satsujin) from 1964.

Lecture

Rembrandt, St. Paul, 1629-1630.

Rembrandt, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. N. Tulp, 1632.

Friedrich Wilhem Murnau, Faust, 1927.

Friedrich Wilhem Murnau, who began his career in fine arts, keeps enhancing his visual skills as one of the most influential film directors, for example in Faust (1927), by studying the appearance and affectation of Rembrandt’s protagonists, his composition and lighting.

Foreshortening

Andrea Mantegna, Lamentation over the Dead Christ, cca. 1490.

Friedrich Wilhem Murnau, Faust, 1927.

In the same film which is both rich in visual references and that had itself became a strong conceptual, poetic and technical reference in cinema, Murnau reconstructs Andrea Mantegna’s perspective foreshortening, although with slight inconsistence due to the differences between the human vision and the camera lens.

Horizon

Werner Herzog, Herz aus Glass, 1976.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Caribean Sea, Jamaica, 1980.

A reconstruction of the classical landscape composition in film (moving image that imitates painting), for example in Werner Herzog’s references to Caspar David Friedreich and Impressionism, is reflected in the motif and concept of the ocean horizon photographed with very long esposure (providing the superposition of a large number of visual values) in Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs.

Illusion

Werner Herzog, Fata Morgana, 1971.

Bill Viola, Chott el-Djerid, 1979.

Sam Mendes, Jarhead, 2005.

Fata Morgana is an atmospheric optical phenomenon that can be photographed. In the film of that name by Werner Herzog (1971) Fata Morgana is a factor of his complex poetic, while in the video Chott el-Djerid (A Portrait in Light and Heat) by Bill Viola it is a part of the meditative-contemplative ambient, and it is æstheticised in Sam Mendes’s film Jarhead (2005).

Reflection

Akira Kurosawa, Heaven and Hell (Tengoku to jigoku), 1963.

Jonathan Demme, The Silence of the Lambs, 1991.

The history of film is largely determined by the adoption and the re-use of themes, (technical) ideas, solutions and procedures. The theme of doppelgänger and its conceptual and visual representation in Akira Kurosawa’s film Heaven and Hell (Tengoku to jigoku, 1963) is reflected in many other films, such as The Silence of the Lambs (1991) by Jonathan Demme.

High-rise

Andreas Gursky, Paris, Montparnasse, 1993.

Paul Greengrass, The Bourne Supremacy, 2004.

One of the key motifs of German experimental music band Einstürzende Neubauten (Collapsing New Buildings) is a problematic relationship between the corporeal, emotional, intellectual human individual and systemic-regimentational tradition of the Modernist utopian urbanism (Le Corbisieur, Ludwig Hilbersheimer, Auguste and Gustave Perret) in contemporary architecture. It is also an æsthetic element of Andreas Gursky’s work, appearing as a blitz-motif in Paul Greengrass’s film The Bourne Supremacy (2004).

Gun in the Hand

Alfred Hitchcock, Spellbound, 1945.

Pater Yates, Bullitt, 1968.

Martin Scorsese, Taxi Driver, 1976.

The materialization of visual perception, of observation as mental process and/or of recording the perceived is one of the oldest and always challenging themes of fine arts, from the rich tradition of portraiture to the eye-movement drawing machine of Jochem Hendricks. In film, it is often manifested through the ‘subjective’ or ‘first-person’ shots in which the gaze is frequently enhanced with the gun, as illustrated above. Among many other examples are Don Siegel’s Count the Hours (1953), John Schlesinger’s Marathon Man (1976) and Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991).

Orthographic Projection

Joel & Ethan Cohen, Fargo, 1996.

Andreas Gefeller, Ohne Titel (Baumschule), Neuss, 2005.

Strict vertical view provides the accent on the abstract visual qualities in the scene, and functions as a premonition of the coming excitements, as in Hitchcock's birdseye perspective.

Andreas Gefeller, Ohne Titel (Ministerium), Düsseldorf, 2005.

Baran bo Odar, Das letzte Schweigen, 2010.

Horizontal view, especially when focused on the architecture and geometrically corrected (like in the High-rise), indicates the systemic and statistic nature of digital culture.

Bathroom

Alfred Hitchcock, Psycho, 1960.

Mark Robson, The Seventh Victim, 1943.

Hitchcock's economical frame composition with the lone bather in the front and the threatening shadow behind the screen in the mid-plane, which initiated the explotation of intimacy and vulerability in thriller genre, could be inspired by the scene from The Seventh Victim created 17 years earlier with the same motivation but with different outcome.[2]

Autobahn

Andreas Gursky, Ruhrtal (Ruhr Valley), 1989.

James Bridges, The China Syndrome, 1979.

Modern society is organized around the principle of personal, atomized transport as opposed to the signifficantly cheaper and more efficient but less profitable concept of public mass transportation. It is reflected in the architectural infrastructure that shapes the landscape of pre-war Germany (and post-war Europe) which adopted the Taylorist and Fordist principles from the United States in the early 20th century.

An Old Mexican Proverb

Luis Buñuel, Viridiana, 1961.

Sergio Leone, Fistful of Dollars, 1964.

Leonardo's Last Supper, via Buñuel's tableaux vivant interpretation in Viridiana, is one of the numerous visual and narrative references in Sergio Leone's spaghetti westerns. In this scene of Fistful of Dollars, a Man with no name - who is actually addressed several times as Joe - discusses an old Mexican proverb that "when a man with a .45 meets a man with a rifle, the man with a pistol will be a dead man". He will soon challenge and disprove it.

-

Kubovy, Michael. The Psychology of Perspective and Renaissance Art, Cambridge University Press, 1988 (online edition 1.1, 2003). ↩

-

Haberman, Steve. The Seventh Victim (Mark Robson, 1943). Audio commentary. DVD. Burbank, CA: Warner Home Video, 2005. ↩