Since 1826 when Joseph Nicéphore Niepce developed the opto-chemical image capturing techniques and named them heliography, that is, since 1839 when he perfected them with his partner Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, was granted the rights by the French government to commercialize them and when British scientist Sir John Herschel gave them their modern name, photography establishes many identities and experiences different histories.

The focus of this lecture is on photography as a specific field of visual arts based on experiment and primarily intended for the gallery/museum system of presentation. The expansion of photography in contemporary art can be traced back to the (re)invention of the new potentials and roles of the photograph in performance art, conceptual art and land art during the 1960’s.

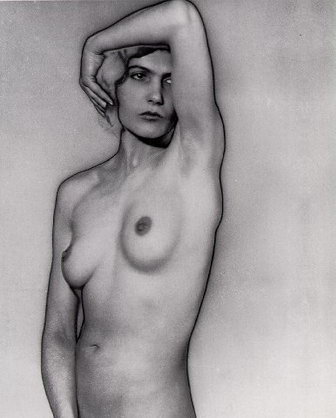

The artists in ‘conventional’ photography generally act from within the medium, mastering and applying various techniques in order to materialize certain motif, theme or idea, while the visual artists who use photography generally approach the medium and its techniques more freely. They often start with a certain idea, intention or concept, and find the photograph or the photographic process most suitable for their realization. This relation between the intention and the medium was influenced by the Modernist avant-guardes, especially by Dada, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray whose words:

They criticize me now for abandoning photography. I have not abandoned photography. I have abandoned the word ‘photography’, which is something totally different. I do not talk about photography just like the writer does not talk about his typewriter.[1]

encapsulate the creative approach to photography in fine art.

Man Ray, Nude, 1929.

Man Ray, Dust Breeding, 1920.

This certainly does not mean that visual artists insist on neglecting the technical aspects of photography but they handle them with flexibility, self-consciousness and expectations that distinguish their works from amateur, family, science, industrial, military, media, fashion or applied photography.

Histories

For an exploration of the histories or various possible stories of photography we could take the similarities, sways and distinctions between four generations of artists: August Sander (1930), Bernd & Hilla Becher (1960), Andreas Gursky (1980) and Idris Khan (2000).[2]

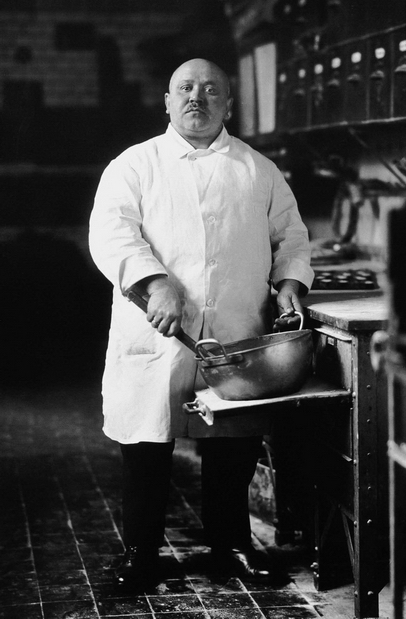

August Sander, Pastry Chef, cca. 1928.

August Sander, Painter (Anton Räderscheidt), 1926.

August Sander was a studio photographer who, relying primarily on his intuition and sense, without academic or scientific backing, took and catalogued some 40.000 photographs of class and social representatives of the German population in his monumental study People of the 20th Century (1910-1930). The idea of Sander’s project and his particular treatment of subjects systematically merge documentary neutrality with empathy.

Bernd & Hilla Becher, Tank, cca. 1960.

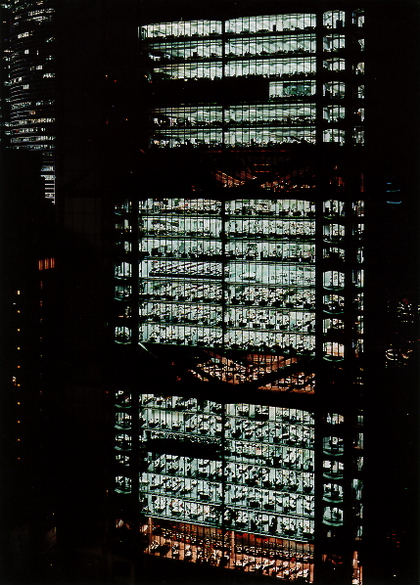

Andreas Gursky, Shanghai Bank Hong Kong, 1994.

But objects can be portrayed as well, especially if they were organized and ordered by human hand. Sander’s systematization, typization, precision and sense for detail we find a generation later in German conceptual photographers Bernd & Hilla Becher whose work comprised pedantic documenting and arranging the variants of architectural structures such as gable sided houses, reservoirs, tanks, pumps and other industrial buildings.

Candida Höfer, National Archive, Naples, cca. 1991.

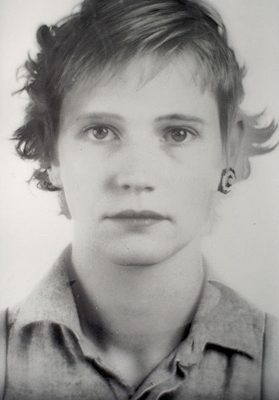

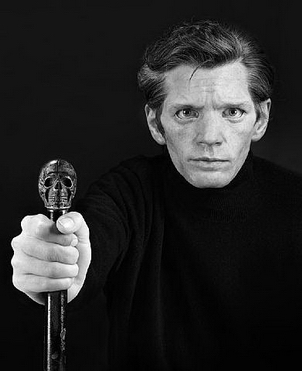

Thomas Ruff, Andere Portrats, 1994-1995.

Using these qualities – distinctive point of view, compositional precision, technical virtuosity and sense for detail – their student at the Düsseldorf art academy Andreas Gursky established complex and ambivalent poetic platform that witnesses and reflects the phenomenology of human civilization at the turn of the 20th century. Thomas Ruff, Thomas Struth, Candida Höfer and other representatives of the Düsseldorf school of photography all achieved something similar in their own specific ways.

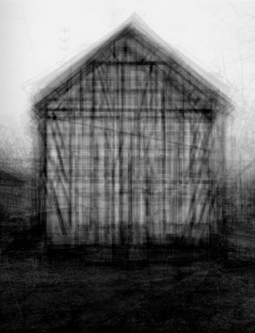

Idris Khan, Gable Sided Houses, 2004.

Jason Salavon, All Playboy Centerfolds '60, '70, '80 i '90, 2002.

Forty years after Bernd & Hilla Becher, British artist Idris Khan makes some kind of (ironic? cynical?) computer-assisted interpretation of their œuvre. He scans all individual photographs of some of Bechers’ series, of which there can be tens or hundreds, and superimposes them in one composite image. The power of visual compression is explored by many other artists. An American, Jason Salavon, for example, developed custom software that calculates the mean average of luminance and chromatic saturation on the pixel-level for a number of superimposed photographs in his Every Playboy Centerfold (1988-1997).

Jim Campbell, Psycho, 2000.

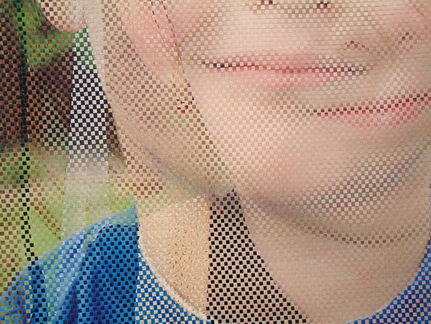

Slavica Panić, Portraits of Diversity (detail), 2004.

Another American artist, Jim Campbell, takes this technique to merge all the frames of films such as Psycho (1960) or Citizen Kane (1941). A Serbian Canadian artist Slavica Panić slyly creates a new kind of photographic superimposition in her series Portraits of Diversity (2004) in which the pairs of large-scale photographic prints were hand-cut into thin horizontal and vertical stripes and then interwoven into final piece.

Identities

A handiwork through which Slavica Panić plays with visual identity brings us to the grand theme of the identity in photography and also to the equally significant question of identity of the photography itself. Both these identities are unstable and depend on a number of factors, especially on the experiential context: the interplay of material circumstances, perceptions and notions.

Gillian Wearing, Me As Mapplethorpe, 2009.

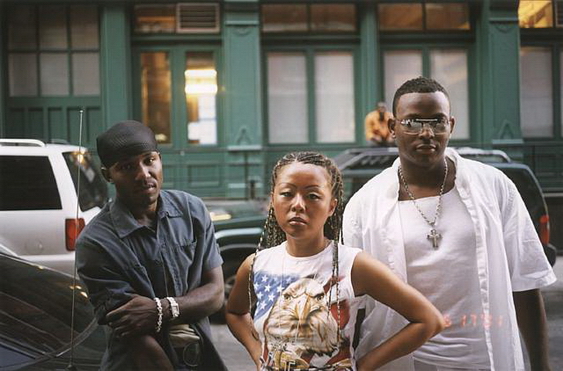

Nikki S. Lee, Hip Hop, 2001.

With minimal imperfections that reveal the process of her own masking for the camera, a British artist Gillian Wearing makes an intricate series of paradoxical self-portraits. By widening that context and combining it with Zelig-like[3] ad hoc mimicry, a Korean artist Nikki S. Lee charges the similar effect with somewhat different consequences and comments. Even the minuscule manipulations in the photographic process can turn into an identity feature of the subject, for example in the work of French artist Valérie Belin (retouching), American artist David Levinthal (macro photography) or Argentinean artist Esteban Pastorino Diaz (tilt-shift photography).

Valérie Belin, Untitled, 2003.

David Levinthal, Hitler Moves East, 1975-1977.

Esteban Pastorino Diaz, Aeroclub Veronica, 2003.

In tilt-shift photography of the exteriors that mimic macro-photography, the long distance and high viewing angle are essential. Using orthographic photography, German artist Andreas Gefeller produces the unpretentious but visually impressive ‘portraits’ of nature influenced by the humans. Collaging process, in which Gefeller seamlessly stitches separate images into a large final image, turns into a metaphor in the work of American artist Chris Jordan.

Andreas Gefeller, Untitled (Holocaust Memorial) (detail), 2006.

Chris Jordan, Plastic Bottles (detail), 2007.

The questioning of the photographic identity can be particularly effective when performed on a basic technological level of physical and chemical generation of the image. A good example is German artist Vera Lutter who converts whole rooms into cameræ obscuræ that, without lenses and in long exposures, capture the images of the outer space and fix them to their inner walls covered with photographic emulsion. Or, the students and professors from University of Texas in Austin whose genetically engineered, photosensitive bacterium Escherichia Coli places their project somewhere between science and art.

Vera Lutter, Frankfurt Airport, 2001.

UT Austin, Photosensitive Escherichia Coli, 2005.

This asserts Michel Frizot’s observation that photography is always between science and art, and reminds us that in assessing not only photography but also art and culture, it is essential to appreciate their composite nature and their interconnectedness with other areas of human creativity. In that sense, another statement by Man Ray:

When my students present their wonderful experiments, their 30x40 cm prints [...] I have to tell them: this is your photograph, but it was not created by you. It was created by professor Carl Zeiss whom it took nine years to calculate the elements of the lens with which you can now get even the slightest details of the face.[4]

indicates the importance of understanding art (that utilizes photography) and making one’s own creative relation with it, as well as the need for an ever-refining, organized support for the young people who are willing to enter such an adventure.

Bibliography

Michel Frizot, A New History of Photography, Könemann, 1999.

Uta Grosenick & Thomas Seelig, Photo Art, Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Charlotte Cotton, The Photograph as Contemporary Art, Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Lothar Schirmer, The Düsseldorf School of Photography, Thames & Hudson, 2009.

William A. Ewing & Nathalie Herschdorfer, reGeneration2, Thames & Hudson, 2010.

Links

http://www.iheartphotograph.blogspot.com

http://www.madeinphoto.fr

http://www.ubu.com

-

Quoted from Man Ray Talks With Pierre Bourgade in Bon soire, Man Ray, P. Belfond, Paris, 1972. ↩

-

In viewing and evaluating the examples in this lecture one should, as always, keep in mind the significant differences between the reproduction of the artwork and its original presentation. ↩

-

Leonard Zelig, a fictional hero of a Woody Allen film Zelig (1983) whose looks, gestures, speech and even skin colour constantly match the persons in his immediate surroundings. ↩

-

Quoted from Man Ray Talks With Pierre Bourgade in Bon soire, Man Ray, P. Belfond, Paris, 1972. ↩