Innovative Combinatorics

I made the anagram for this lecture’s video introduction using Internet Anagram Server, one of the web applications for semantic combinatorics. The music for the intro is my remix of the songs which are themselves remixes of other popular songs.[1] These are just two in a myriad of possible illustrations that language and art are the systems of innovative combinatorics, and that thinking process is partly based upon the comparison between the known and the unknown, the existing and the new – in other words upon the analogy making.[2] Innovative combinatorics is essential in all areas of creativity, from social and political relations, through art, to technology and science,[3][4][5] which is wittily addressed in Kirby Ferguson’s online documentary Everything is a Remix (2011).

Innovative combinatorics in art appears in various procedures ranging from reminiscences, reflections and dedications, through citations, interpretations and remixes, to free copies, imitations, forgeries and rip-offs.[6][7][8] With the recurrence of themes, motifs, forms and techniques, these procedures are among the key factors in art, and art histories can in a way be regarded as the stories about changes in innovative combinatorics. Artistic references induce pleasure in the recognition of source materials, concepts and models, and especially in their interrelations with other poetic elements.

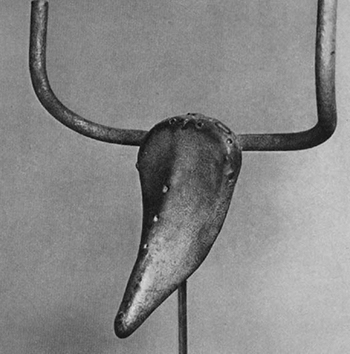

Pablo Picasso, Head of a Bull, 1942.

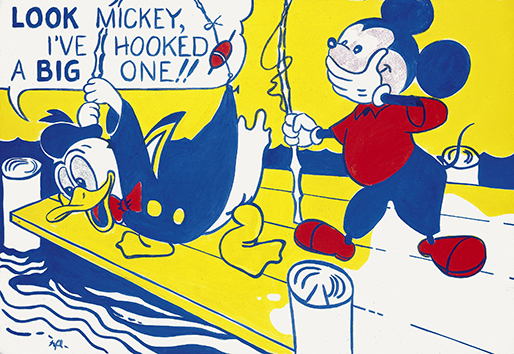

Roy Lichtenstein, Look Mickey, 1961.

Artistic use of the materials from popular culture has been legitimized in different ways throughout the 20th century—from Cubism and Dada, through Pop-Art, Fluxus and Conceptual Art, to Postmodernism in which it became a genre in itself—and today exists in many artistic strategies and approaches.[9] It usually attracts public and mass-media attention in instances when an artwork which references some commercially successful copyrighted artifact also becomes commercially prominent, inciting the financial conflict between two or more parties.

(Re)creativity

The term (re)creativity specifically designates the use of digital technology for transforming the preexisting materials in order to create the new artwork. It was introduced by Lawrence Lessig who is widely known for his studies and activism in legal, political and social aspects of copying, creative combinatorics and intellectual property issues in digital culture.[10] Utilizing the conceptual, procedural, formal and expressive potentials of computer processing of all cultural phenomena that can be digitized, (re)creativity unfolds in a highly diverse artistic production. Therefore I focused this lecture on projects that work with photography, film, television and the Internet.

Interventions

Fine examples of (re)creativity are Douglas Gordon’s installation 24 Hour Psycho (1993) in which he slowed down Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) from the original 1 hour and 49 minutes to 24 hours,[11] and Martin Arnold’s project Deanimated (2002) in which he gradually and systematically removed the human figures from the 1941 B thriller The Invisible Ghost so that the final 15 minutes of the film show everything but the actors.[12]

Douglas Gordon, 24 Hour Psycho (double projection), 1993.

Martin Arnold, Deanimated, 2002.

With custom made AI software for computer vision, Roger Luke DuBois aligns the portraits of various sizes and compositions to the eyes of the depicted person. In video Play (2006) he used portraits of all the playmates of the month from the first 50 years of Playboy magazine, and in (Pop) Icon Britney (2010) all portraits of Britney Spears from her photographs and music videos.

Statistical Transformations

Jason Salavon develops custom software which statistically processes various media. For the Amalgamations series (from 1997) he uses mean- and median-based image averaging. In Every Playboy Centerfold 1988-1997 (1998) he merges all Playboy centerfolds from 1988 to 1997 into one image, and in Every Playboy Centerfold, the Decades (Normalized) (2002) Playboy centerfolds by the decade from the 1960’s to the 1990’s. Another work from the series, The Class of 1967 and 1988 (1998), consists of four composite portraits created by merging photographs of all the alumni and all the alumnae from his mother’s and his own graduation yearbooks respectively. In 100 Special Moments (2004), Salavon merges the sets of one hundred conventionally themed photographs taken from the Internet: kids with Santa Claus, junior baseball league, the wedding and the graduation. In Portrait (2010) he makes four composites merging the reproductions of all the portraits by Frans Hals, Rembrandt van Rijn, Antonis van Dyck and Diego Velasquez in the Metropolitan museum.[13]

J. Salavon, The Class of 1967, Men.

Jim Campbell applies his own custom software for image averaging to merge all the frames from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) and Hitchcock’s Psycho in his Illuminated Average Series (2000 and 2009).

Jim Campbell, Illuminated Average Series: Citizen Kane, 2000.

Jim Campbell, Illuminated Average Series: Psycho, 2000.

By compressing and averaging multiple images, these artists eliminate the details, emphasize the coloristic and compositional trends in the original materials, and indicate the evolutionary aspects of aesthetic preferences.

Infographic Studies

Statistical transformations of spatial, temporal, visual, semantic and narrative qualities in infographics provide new ways for envisioning and evaluating cultural artifacts.

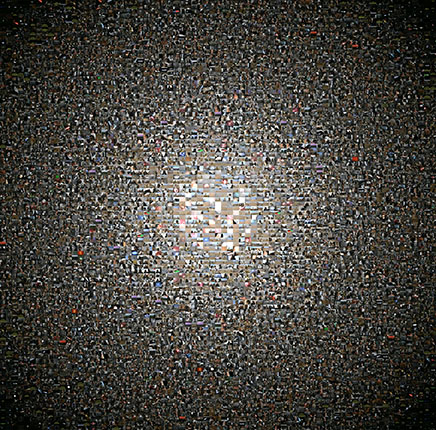

In a series of prints entitled The Grand Unification Theory (1997) Jason Salavon infographically organizes the visuals of popular movies. He extracts the frames (one frame per second) from Star Wars (1977), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and Deep Throat (1972) respectfully, and arranges them radially according to brightness, from the brightest images in the center to the darkest at the periphery.

Jason Salavon, The Grand Unification Theory: Star Wars, 1997.

Jason Salavon, The Grand Unification Theory: Star Wars (detail), 1997.

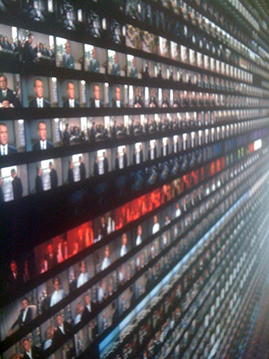

With simple sequential arrangement of the frames in Cinema Redux (2004) print series, Brendan Dawes reveals the overall visual organization and editing dynamics of popular films. He extracts one frame per second of the film and positions them sequentially in a composition 60 frames (one minute of original film) in width and length depending on the film runtime. For the 2008 opening of Tyneside cinema, Daniel Shiffman animated this process in the video wall titled Filament which successively shows and shifts the sequence of 1400 frames (50 seconds) from Tom Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998). Marco Brambilla applies the same principle of sequentially animating frames from the film sequences in his Flashback (POV) (2010).

B. Dawes, Cinema Redux: Vertigo (detail), 2004.

Daniel Shiffman, Filament (detail), 2008.

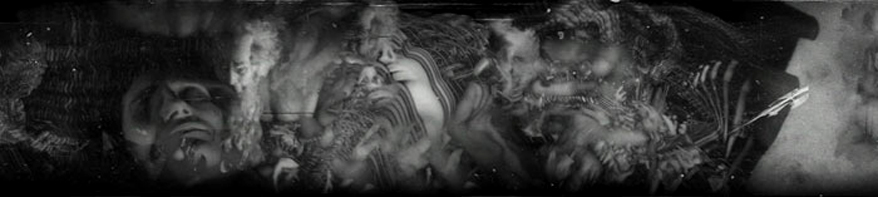

In Motion Extractions / Stasis Extractions project (2007-2009), Kurt Ralske elaborates and additionally estheticizes the sequential extraction of film frames. He creates prints by extracting and inter-dissolving the frames from selected films[14] according to the criterion of camera movement, movement of actors and/or objects in the scene: Stasis Extractions is a set with static imagery, and Motion Extractions is a set with the imagery that contain movement.

Kurt Ralske, Motion Extraction: Faust (1927) (detail), 2007-2009.

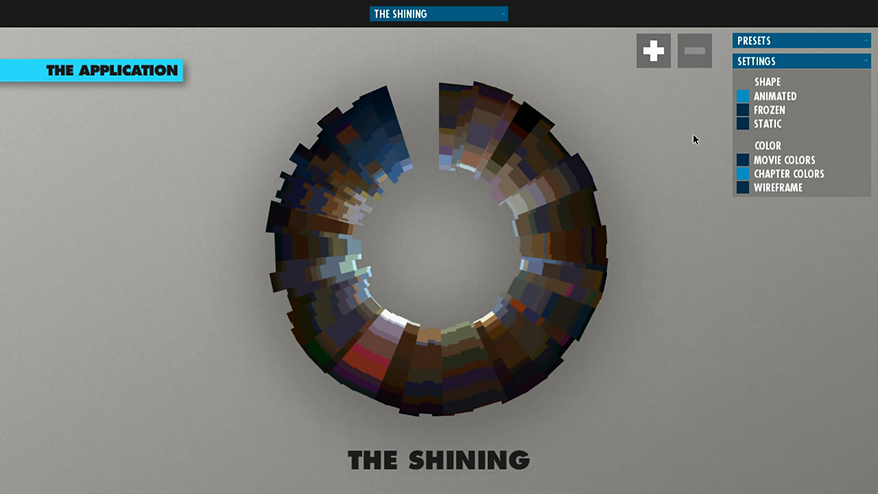

Fourteen years after Salavon’s The Grand Unification Theory series, Frederic Brodbeck advances the infographic processing of film in his graduation project Cinemetrics (2011) comprising a Python application, a book and a poster series. The application provides interactive visualizations, analyses and comparisons of the loaded films according to a number of criteria such as duration, average luminance and chromatic values of the imagery, dynamics of movement in sequences, original version of a film vs. remakes, all films by the same director, films by different directors, etc.

Frederic Brodbeck, Cinemetrics, 2011.

Infographic art projects Acceptance (2012) and Hindsight is Always 20/20 (2008) by Roger Luke DuBois are based on the semantic analysis of speech. Acceptance is a two channel generative video that matches and synchronizes the sequences of 2012 nomination acceptance speeches by Barack Obama and Mitt Romney according to the words and phrases they use (which are 80% identical). Hindsight is Always 20/20 is a series of prints designed as Snellen-style eye charts showing the top 66 characteristic words of each American presidents’ State of the Union addresses, from George Washington through George W. Bush. Word size reflects its frequency in each speech.

Culture as a Database

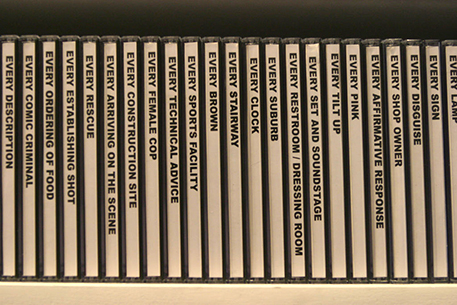

Statistical systematization in infographics also helps us recognize the regularities, routines and clichés in mass-produced culture. Jennifer & Kevin McCoy’s installation Every Shot, Every Episode (2001) is a collection of all shots from the TV serial Starsky and Hutch, categorized according to 278 formal and narrative criteria: every zoom in/out, every architecture, every disguise, every female police officer, etc. Shots in each category are successively arranged on DVDs that the visitors play freely on two or three parallel displays. Their installation Every Anvil (2002) applies the same method to the cartoons from the Looney Tunes series, with 20 categories: every profuse sweating, every fall, every sneaking, every explosion, etc.[15]

Jennifer & Kevin McCoy, Every Shot, Every Episode, 2001.

Jennifer & Kevin McCoy, Every Shot, Every Episode (detail), 2001.

Three video projections in Marco Brambilla’s installation Sync (2005) were created by matching and linking numerous short sequences (2 sequences per second) from the movies and television programs which show theater audience, sexual act and fighting. These self-referential structures essentialize the narrative and formal models of their source materials and thematize the three essential components of screen culture: isolated or distanced viewing, sex and violence.

In his short films Copy Shop (2001) and, most notably, Fast Film (2003), Virgil Widrich intelligently expands the possibilities for reproducing and interpreting the accumulated imagery in order to accentuate both the obsessions and stereotypes of conventional film. Fast Film was created by making paper prints of all the frames from the selected movie sequences, which were then reshaped, warped and torn into complex new animated compositions. This approach provides elegant, witty and engaging critical condensation of the key narrative themes in conventional film such as romance, abduction, chase, fight and deliverance, compressed into exciting 14 minutes of runtime.

These projects innovatively explore the ways for the advancement of our understanding of animation and film (as a special kind of animation), of their experiential and cultural effects, and their social roles.

Exploiting this methodology, primarily the advantages of digital editing, György Pálfi makes a feature-length movie Final Cut: Ladies and Gentlemen (2012) out of sequences from 450 popular films and cartoons. Interestingly, the film critics praised this creation as ‛an ode to cinema’[16] even though (or exactly because) its concept basically avoids the questioning of clichés, conventions and overall creative scarcity of conventional film, and glorifies them instead.

Society as a Database

Not only cultural artifacts, but all social structures and relations relying on frequent, predictive exchange and processing of large quantities of data can be conceptualized, organized, envisioned and manipulated as databases. Economic systems and institutions such as industry, marketing, advertising, mass-media, banks, insurance companies, and information services all operate statistically. They virtually approach and assess their clients’ persons, groups and categories as more or less complex datasets that are handled through programmable routines.[17] This is most evident in the interface of social networks, whose design and functionality delineate their statistical logic or clumsily try to hide it, while some art projects reveal it in a humorous, often spectacular and provocative ways.

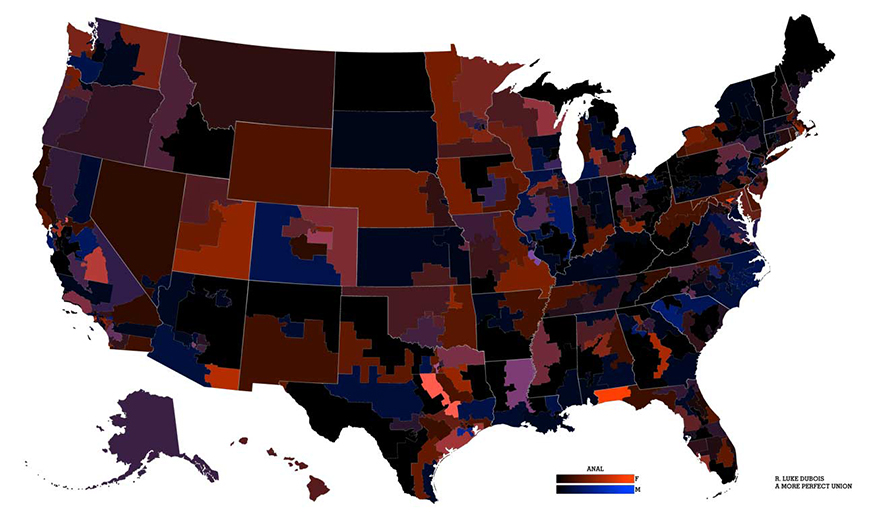

In his project A More Perfect Union (2010-2012) Roger Luke DuBois signed up to 21 US dating websites, sampled 19 million profiles from them, and geographically arranged the most frequent keywords (using zip codes). He then made 43 maps of the USA. Federal maps use the red/blue brightness/saturation ratio to show the relations between female and male preferences for the most frequent keywords (blonde, cynical, funny, happy, open-minded, lonely, optimist, etc.) in each state. In state and city maps, DuBois replaced the names of cities, towns and streets with the most frequent keywords in dating profiles of local citizens. He thus created a specific socio-cultural outline of contemporary USA, based upon the preferred identities and more or less intimate aspirations of the population.

Roger Luke DuBois, A More Perfect Union: Federal, Anal, 2010-2012.

Working on this project, DuBois noticed a profile of another person who, like him, signed up and frequented dating websites with conflicting gender identities, lifestyles and sexual orientations. He found out that it was a musician from Oakland, CA, who uses keywords and phrases from dating websites as lyrics in her songs. With the idea to establish intimate relationship as an artwork, he invited her to a date and travelled from New York to Oakland. They went out for a coffee, but it did not work out.[18]

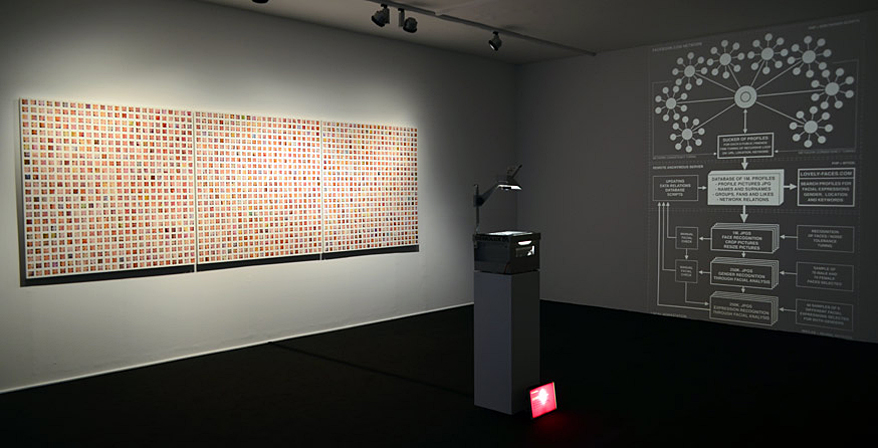

There are interesting parallels between A More Perfect Union and Face to Facebook project from the same year (2010) by Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico. Face to Facebook is an internet robot which took one million Facebook user profiles, selected 250.000 out of these and, applying the face recognition algorithm to the profile photos, classified them according to various criteria such as relaxed, egocentric, smug, pleasant, etc. Then it uploaded the 250.000 selected profiles to a fictitious dating website called Lovely Faces.

Paolo Cirio & Alessandro Ludovico, Face to Facebook (installation view), 2010.

Collage and Rearrangement

Surely, formal transformations do not have to be statistically based in order to open new perspectives for viewing and understanding cultural artifacts, and to create new experiences by abstracting or concretizing the source materials. All the artists need for achieving that are the means to systemically organize and programmatically manipulate digitized data.

In Rear Window Timelapse (2011), for example, Jeff Desom spatially arranges and synchronizes separate shots from Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) into a unified video collage simultaneously showing the events in the backyard and in the neighboring flats observed by the protagonists. It converts a selective, linearly edited view into a panoramic platform.

Jeff Desom, Rear Window Timelapse, 2011.

In their application Life in a Day Gallery (2010), Jono Brandell and George Michael Brower use the new ways of organizing, presenting and distributing video/film, introduced by sharing websites such as YouTube. The application accompanies the crowdsourcing[19] film project Life in a Day (2010) by Kevin Macdonald, which is a structurally conventional feature[20] created by linear editing of some 10.000 videos uploaded to YouTube on 24 July 2010 per authors’ announcement. In contrast, and consistently to the technological and conceptual logic of the whole project, Life in a Day Gallery offers a variety of options for interactive access to all 80.000 video uploads, their selection, arrangement and successive or parallel screening.

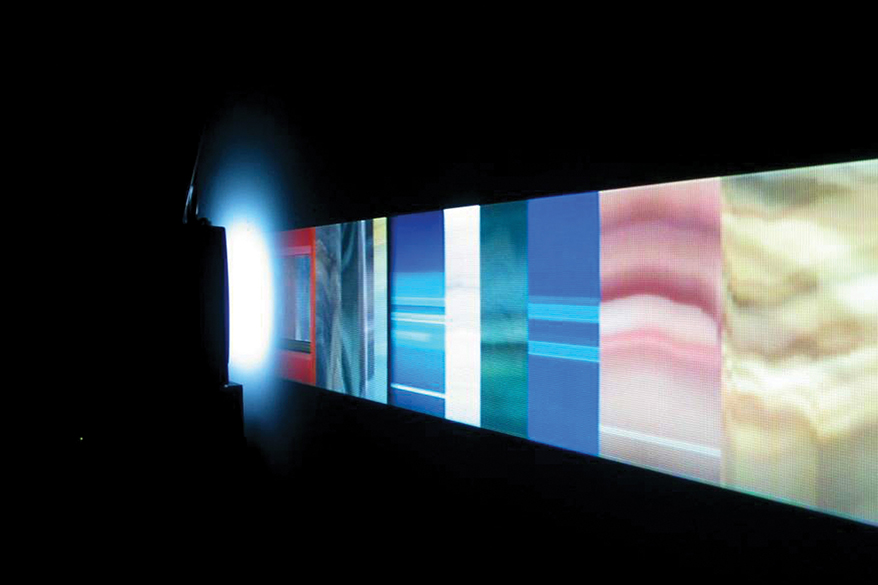

Traditional TV broadcasting, however, remains a potent source for (re)creativity. In We Interrupt Your Regularly Scheduled Program… (2003) installation by Osman Khan and Daniel Sauter, a signal from the cable TV receiver is simultaneously sent to a computer and to a TV screen facing the gallery wall (so, instead of clear image, the audience can see its soft reflex). The real time slit-scanning software in the computer collapses every frame of the TV program[21] into a vertical line averaging the chromatic and luminance values of the whole picture, and continually projects it left to right on the gallery wall besides the TV screen. The audience can flip the channels with remote control thus creating a continuous abstract animation in which the cuts and channel changes show as sharp verticals, and zooms and other compositional changes as curves.

Osman Khan & Daniel Sauter, We Interrupt Your Regularly Scheduled Program..., 2003.

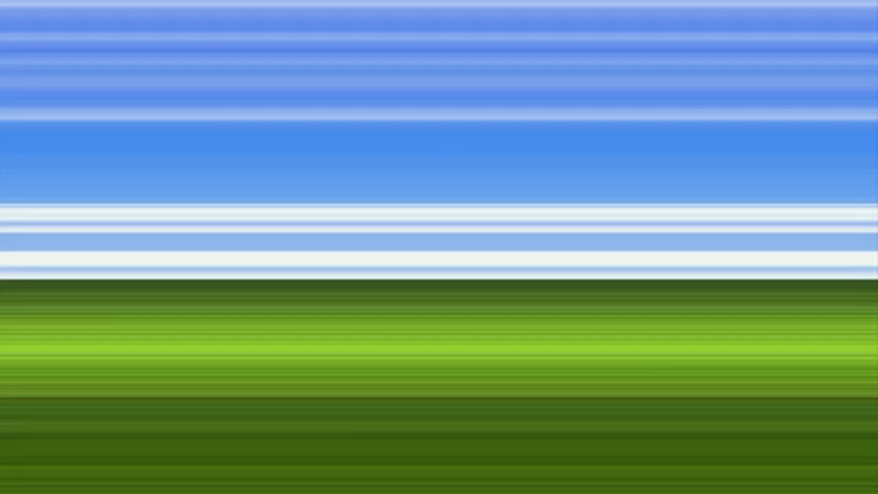

Ambient Environments: Windows XP (2013) video by Phillip Stearns is one of the recent glitch artworks that use slit-scanning. It converts the default Windows XP desktop picture (3840px wide) into a video of 3840 frames (2 minutes and 8 seconds with 29.971 fps). The picture is scanned left to right into 3840 vertical lines 1 pixel wide, and each line is stretched into an image of 640 by 360 pixels. The images are then successively animated and synchronized with a slowed-down Windows XP default startup sound into a final video.

Phillip Stearns, Ambient Environments: Windows XP, 2013.

(Re)creativity = Software?

Examples in this lecture may suggest that the procedural elements of (re)creativity, and of innovative combinatorics in general, may be presented as algorithms and converted into program code. Indeed, modern video editing applications have options for time/speed control, scripts for precise object removal and for sequential frame extraction; imaging software offer actions for mean- or median-based layer blending, creative coding environments feature real time slit-scanning libraries,[22], and many mobile apps turn the camera into a slit scanner.

But the procedural steps of any creative process, when clearly defined, can be systematized, algorythmized, and coded. Plasticity and adaptability in mimicking natural processes are the key factors of universal computing machine which lays the conceptual foundation for modern computers.[23][24] Achieving that plasticity and adaptability, however, is itself a creative process which requires ingenuity, team work, interdisciplinary research, understanding of accumulated knowledge, and learning. Every time a previously incomputable natural phenomenon or creative process gets algorythmized, it is human intelligence doing the complex job of scrutinizing, symbolically structuring and encoding it into programmable system. This relationship between human creativity and human-built or human-programmed simulations of creativity reveals the essential flexibility of human mind in allowing itself to be influenced by the technology and simultaneously absorbing, transforming, adapting and repurposing it.

This lecture's examples also remind us that creativity in visual arts integrates three modes of learning: visual (perception, abstraction, intuition and insight), interactive (physical experience and coordination), and symbolic (procedure, language and text). Visual and interactive modes have been traditionally favoured in art education, while the symbolic mode is more frequent and better distinguished in artistic research and communication than in production.[25] To the artists who use coding, the symbolic conditionality of programming languages is often a generous source of frustrations, but also a drive for tightening their methodology, for improving their precision and discipline. Combined with the unpredictable motives and circumstances of analogy making, these qualities of procedural thinking enrich the expressive and cognitive potentials of innovative combinatorics, illustrating the breadth of human creativity and the complexity of digital culture.

-

The Doors O'Hell by John Oswald (Elektrax, 1991), I Hate the 80's by Duran Duran Duran (Very Pleasure, 2004), Ludwig Van Beethoven 7th and Public Enemy / James Brown by John Oswald (Plunderphonic, 1988), The Queen and I by The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (KLF) (WTF's Going On, 1987) and The Number Song (Cut Chemist Party Mix) by DJ Shadow (Entroducing, 1996). ↩

-

Hofstadter, Douglas, / Emmanuel Sander. Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. New York: Basic Books, 2013. ↩

-

Pinker, Steven. Writing About Science. New York: Big Think, 2012. ↩

-

Rutherford, Adam. Creation, Synthetic Biology and Hip-Hop. Dublin: Science Gallery, November 2013. ↩

-

Rutherford, Adam. Creation: How Science Is Reinventing Life Itself. London: Penguin Current, 2013. ↩

-

Reynolds, Simon. “You Are Not a Switch: Recreativity and the Modern Dismissal of Genius.“ Slate Book Review, 5 October 2012. ↩

-

Boon, Marcus. In Praise of Copying. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. ↩

-

Šuvaković, Miodrag. Pojmovnik suvremene ujetnosti. Zagreb / Ghent: Horetzky / Vlee & Beton, 2005. ↩

-

Lessig, Lawrence. “Laws That Choke Creativity.“ TED. 2007. ↩

-

Fried, Michael. Douglas Gordon. Berlin: Kerber, 2012. ↩

-

Matt, Gerald, / Thomas Miessgang. Martin Arnold: Deanimated. Wien / New York: Kunsthalle Wien / Springer Verlag, 2002. ↩

-

Ewing, William A. Face: The New Photographic Portrait. London: Thames & Hudson, 2006. ↩

-

Student of Prague (1913), Faust (1927), Citizen Kane (1941), The Seventh Seal (1957), Alphaville (1965), 2001 Space Odyssey (1968) etc. ↩

-

This thematically structured editing style became an Internet meme known as supercut. ↩

-

Q.P. Final Cut - Ladies and Gentlemen, an Ode to Cinema. Festival de Cannes. 2012. ↩

-

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. ↩

-

DuBois, R. Luke. Digital Arts @Google: R. Luke DuBois & Scott Draves. Google. 2010. ↩

-

Crowdsourcing is an aggregation method based upon the relatively simple, voluntary participation of a large number of individuals for the realization of complex projects, which became particularly feasible and popular with the Internet. It is often used in art projects (crowdartmaking) such as Man With a Movie Camera: The Global Remake (2008) by Perry Bard, Bicycle Made For Two Thousand (2009) by Aaron Koblin and Daniel Massey, and Exquisite Clock (2009) by Joao Henrique Wilbert. ↩

-

Life in a Day follows the tradition of ‛film as a global/urban simphony’ genre initiated by experimental films such as Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921), Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (1926), Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (1927), Andre Sauvage’s Etudes sur Paris (1928), Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera (1929) and Walter Ruttmann’s Melodie der Welt (1929). ↩

-

Every horizontal line of the TV frame is collapsed into a pixel with average luminance and chromatic value. The NTSC standard, in which the installation is originally produced, has 29.97 frames per second, so one image/vertical line is 0.033 seconds in duration. ↩

-

Reas, Casey, Chandler McWilliams, / LUST. Transform: SLIT-SCAN. Form+Code in Design, Art, and Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press. 2013. ↩

-

David, Martin, / Davis Martin. The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. ↩

-

Watson, Ian. The Universal Machine: From the Dawn of Computing to Digital Consciousness. New York: Springer, 2012. ↩

-

Victor, Bret. "Media For Thinking the Unthinkable." MIT Media Lab, 4 April 2013. ↩

The adapted lecture transcript was published in:

Going Digital: Innovations in Contemporary Life Conference Proceedings, STRAND - Sustainable Urban Society Association, Belgrade, 2015. ISBN 978-86-89111-08-08, pp. 29-36.

Review of the Faculty of Fine Arts: Art and Theory, Volume 1, No. 1, 2015, pp. 84-91.