Innovative

Cognition and language are the systems of innovative combinatorics, partly based upon the comparison between the known and the unknown, the existing and the new, that is, upon the analogy-making.[1] Innovative combinatorics is essential in all human activities: socialization, relations, art, technology and science.[2][3] Innovative combinatorics in art appears in various procedures ranging from reminiscences, reflections and dedications, through citations and remixes, to imitations, forgeries and rip-offs.[4][5]

Artistic appropriation of popular culture has been legitimized in different ways throughout the 20th century, and today exists in many strategies and approaches. The use of expressive potentials of digital technology for transforming the preexisting materials into the new artwork is often designated as (re)creativity.[6]

Interventionist

Fine examples of interventionist (re)creativity are Douglas Gordon’s installation 24 Hour Psycho (1993) in which he slowed Hitchcock’sPsycho (1960) down to 24 hours, and Martin Arnold’s film project Deanimated (2002) in which the visual and acoustic manifestations of actors were gradually rotoscoped out of the 1941 B thriller The Invisible Ghost so that the final 15 minutes contain everything but the actors.

Martin Arnold, Deanimated, 2002.

Calculated

Statistical systematization in infographics reveals the formal, semantic and narrative regularities and clichés in cultural production, providing new ways for evaluating its effects and social roles.

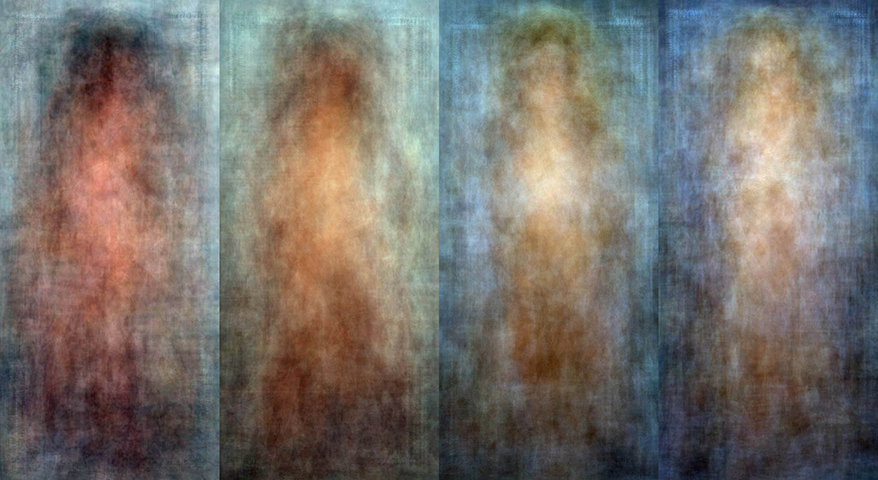

By compressing and parametrically averaging images from various media in the Amalgamations series (from 1997), Jason Salavon eliminates the details and emphasizes the coloristic and compositional trends in his source materials. In Every Playboy Centerfold, the Decades (Normalized) (2002) Salavon merges all Playboy centerfolds by the decade from the 1960’s to the 1990’s, while in 100 Special Moments (2004), he merges the sets of one hundred conventionally themed photographs taken from the Internet: kids with Santa Claus, junior baseball league, the wedding and the graduation. In a series of prints entitled The Grand Unification Theory (1997) Salavon organizes the visuals of popular movies by extracting one frame per second and arranging them radially according to brightness.

Jason Salavon, Every Playboy Centerfold, the Decades (Normalized), 2002.

With sequential frame arrangement in his Cinema Redux (2004) print series, Brendan Dawes reveals the overall visual organization and editing dynamics of popular films. He extracts one frame per second from selected films, and positions them in a composition 60 frames in width and length depending on the film runtime. In Motion Extractions / Stasis Extractions project (2007-2009), Kurt Ralske elaborates and further aestheticizes the sequential frame arrangement by isolating and inter-dissolving the film frames with registered motion (Motion Extractions) and static frames (Stasis Extractions). Fourteen years after Salavon’s Grand Unification Theory, Frederic Brodbeck advances the infographic processing of film in his graduation project Cinemetrics (2011) – an application for interactive visualization, analysis and comparison of films according to a number of criteria such as duration, chromoluminant values of the scene, and editing dynamics.

Self-Assured

Jennifer & Kevin McCoy’s installations Every Shot, Every Episode (2001) and Every Anvil (2002) are realized as supercut collections of shots from the TV serial Starsky and Hutch, and from Looney Tunes cartoons respectfully, categorized according to various criteria: zooming in/out, disguising, female police officers, profuse sweating, falling, sneaking, explosions, etc. Each category is saved on a separate DVD that visitors can play on parallel displays and get surprised by the banality, rigidity and uninventiveness of the applied formal solutions in any of them. The three video channels in Marco Brambilla’s supercut installation Sync Sex/Watch/Fight (2005) were created by matching numerous short sequences from the movies and television programs. Self-referentially repeating the narrative and formal models of their source materials, these videos address the essential components of screen culture: isolated viewing, sex and violence. Acceptance (2012) by Roger Luke DuBois is a two channel generative video in which the 2012 nomination speeches by Barack Obama and Mitt Romney are mutually matched and synchronized by to the words and phrases they use, which are 80% identical but distributed differently.

Roger Luke DuBois, Acceptance: Obama, 2012.

Roger Luke DuBois, Acceptance: Romney, 2012.

Communicative

Not only cultural production, but all social structures relying on frequent, massive and predictive exchange can be conceptualized and manipulated as databases. Industry, marketing, advertising, mass-media, finances and information services all operate statistically. They virtually approach and assess their clients as programmatically handled datasets.[7] This statistical logic is most evident in the interface design and functional dynamics of social networks which clumsily try to hide it, while the artists reveal it in humorous and provocative ways.

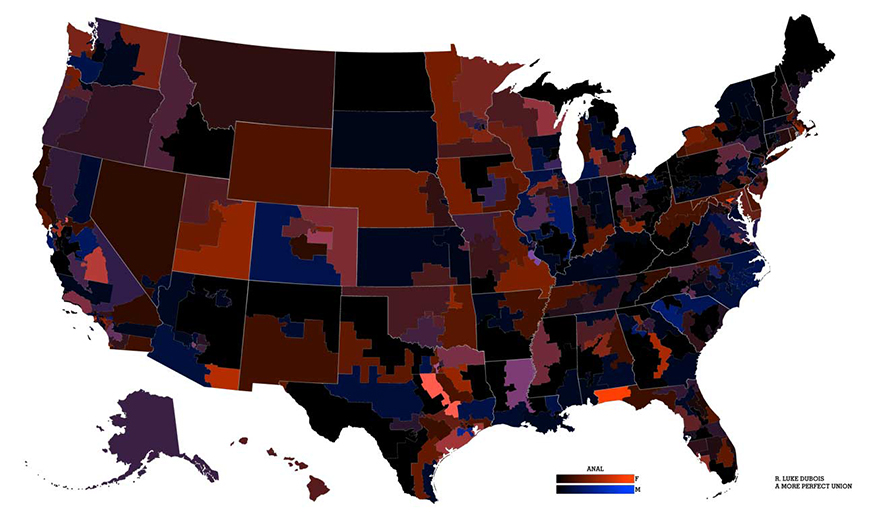

Roger Luke DuBois, A More Perfect Union: Federal, Anal, 2010-2012.

In A More Perfect Union (2010-2012), DuBois creates a complex socio-cultural outline of contemporary USA, based upon the preferred identities and intimate aspirations of the population. He sampled 19 million user profiles from 21 US dating websites and arranged them geographically by the most frequent keywords in order to make 43 maps. Federal maps show the relations between female and male preferences for the most frequent keywords in each state using red/blue hue and brightness/saturation ratio. In state and city maps, the names of cities, towns and streets are replaced with the most frequent keywords in dating profiles of local citizens. There are interesting parallels between A More Perfect Union and the internet robot Face to Facebook (2010) by Paolo Cirio and Alessandro Ludovico, which took one million Facebook user profiles, selected 250.000, classified them according to various facial characteristics and uploaded to a fictitious dating website Lovely Faces.

Effective

Abstracting or condensing the cultural artifacts does not have to be statistically based in order to open new perspectives for assessment. All the artists need are the tools for systematic organization and manipulation of the data.

Virgil Widrich, Fast Film, 2003.

In Fast Film (2003), Virgil Widrich intelligently combines the analogue reproduction and unconventional interpretation of accumulated imagery to accentuate the obsessions and stereotypes of conventional cinema. Fast Film was created by making paper prints of all frames from the selected movie sequences, which were then reshaped, warped, torn and composed into complex new animations. This approach provides an elegant, witty and engaging critical condensation of the key cinematic themes into exciting 14 minutes of runtime. In Rear Window Timelapse> (2011), Jeff Desom digitally arranges and synchronizes the linearly edited shots from Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954) into a unified panoramic video collage which simultaneously shows the events in the backyard and in the neighboring flats observed by the protagonists.

Creative

These examples may suggest that the procedural elements of innovative combinatorics can be presented as algorithms and converted into code. Indeed, many standard computer applications today provide most of the functions for which the artists originally had to develop their own software. But the procedural elements of any creative process, when clearly defined, can be algorythmized and coded because plasticity and adaptability in mimicking natural phenomena are the defining factors of universal computing machine which lays the conceptual foundation for modern computers.[8] Achieving that plasticity and adaptability is itself a specific creative process requiring ingenuity, interdisciplinary research, understanding, learning and insight.

These examples also remind us that creativity in fine arts integrates three modes of learning: visual, interactive and symbolic. Visual and interactive have been traditionally favored and better distinguished, while the symbolic mode is more frequent in research and communication than in production.[9] To digital artists, the symbolic conditionality of programming is often a generous source of frustrations, but also a drive for tightening their methodology, for improving the precision and discipline of procedural thinking. Combined with the unpredictable motives and circumstances of analogy making, the creativity in programming creative processes reveals the fundamental flexibility of human mind to simultaneously invent the technology, absorb it, adapt to it, repurpose and transform it as needed.

-

Hofstadter, Douglas / Emmanuel Sander. Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. New York: Basic Books, 2013: 17. ↩

-

Ferguson, Kirby. Everything is a Remix. 2011. http://www.everythingisaremix.info/. ↩

-

Pinker, Steven. Writing About Science. New York: Big Think, 2012. ↩

-

Boon, Marcus. In Praise of Copying. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. ↩

-

Reynolds, Simon. „You Are Not a Switch: Recreativity and the Modern Dismissal of Genius.“ Slate Book Review, 5 October 2012. ↩

-

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. ↩

-

David, Martin, / Davis Martin. The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000. ↩

-

Victor, Bret. „Media For Thinking the Unthinkable.“ MIT Media Lab, 4 April 2013. ↩

Formless: Fluid Reality in New Media Art exhibition, Museum of Contemporary Art, Belgrade, 15 August 2015.